The site of the Roman settlement at Vagnari lies about 15 kilometres northwest of Gravina in Puglia in agricultural land planted annually with wheat. The site was discovered by Alastair Small in field surveys in the Basentello valley in 2000. Very near and to the north of Vagnari, the Via Appia was located, and this major Roman artery, as well as a nearby east-west drove way (tratturo) from upland Lucania to Gravina used for transhumance, must have contributed considerably to the prosperity of Vagnari and even to the selection of this location for settlement.

The University of Sheffield conducted archaeological fieldwork in the central village (vicus) of the Roman imperial estate from 2012 to 2019. The Roman cemetery, separated from the vicus by a ravine, has been the focus of ongoing investigations by McMaster University since 2003.

Recent excavations in the vicus have revealed a late Republican settlement of the second century B.C. that may have been established by Roman investors expanding into Apulia after the Roman conquest in the third century. This settlement, and others in the territory of the Peuceti, would have been connected to and perhaps dependent on Silvium, today’s Botromagno. This landholding at Vagnari then became the property of the emperor in the early first century A.D.

Tile stamps naming a slave of the emperor who oversaw the production of building ceramics attest to the imperial ownership of the estate. Archaeological evidence indicates that the period between the late first and the mid-third century A.D. was the most active and productive phase of occupation in the vicus at Vagnari.

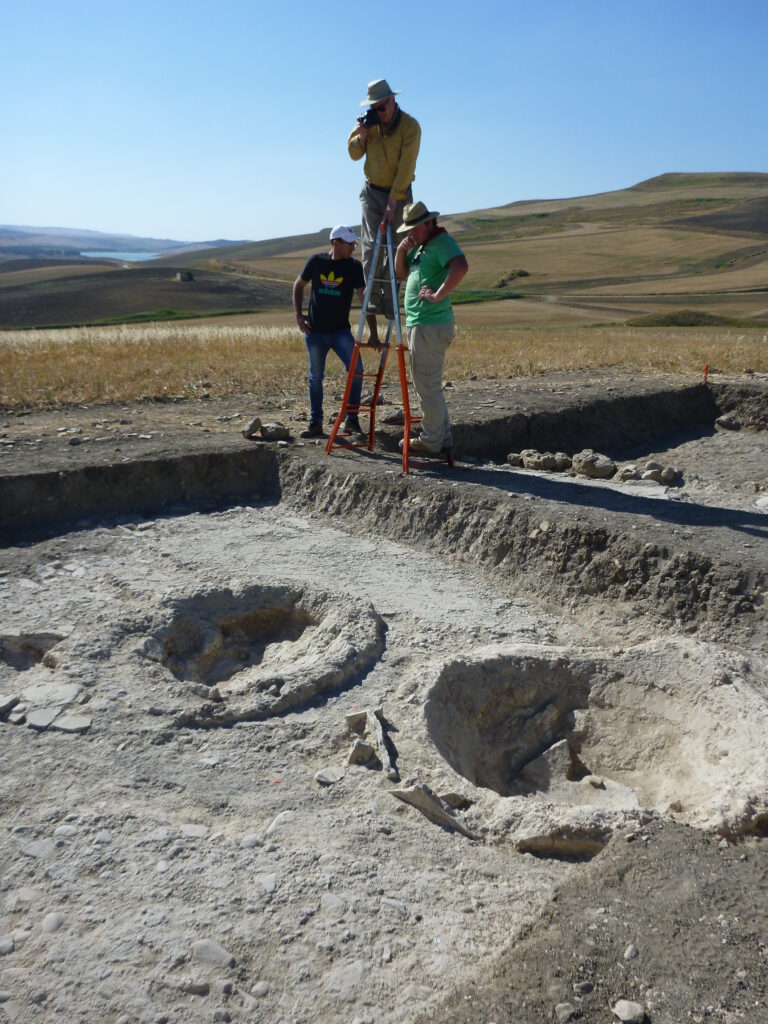

Fig. 3 Drone photo of the Vagnari plateau, looking north-west to the Monte Marano and the Diga di Basentello (Photo G. Ceraudo and V. Ferrari, Laboratory of Ancient Topography and Photogrammetry of the University of Salento)

The imperial estate had a broad economic basis, ranging from cereal crop cultivation to metal-working and tile production, with further diversification to include viticulture in the second century A.D., all of which have left traces in the vicus. Various structures for the processing and storage of produce from the estate lands have been explored, and these include a winery or cella vinaria with large dolia inserted into the winery floor. The fourth century witnessed the decline and abandonment of the vicus. A much smaller settlement grew up south of the ravine that was occupied until the late fifth century.

Prof. Maureen Carroll

Department of Archaeology – University of York – Kings Manor – York YO1 7EP – United Kingdom