Between 1998 and 1999, our restoration of the eight tombs — restored in 1853, by the Turin architect Luigi Canina, that were situated between Roman Miles IV and V of the Appia road — meant that we had to revisit his architectural idea (Filetici, Paris 2017). His innovative proposal for an open-air museum is still today very topical. Travelling along the ancient road by horse-drawn carriages, 19th-century visitors were able to view the archaeological findings where he had reassembled and mounted them on the facades of the buildings, preserving them in situ in a way that would also make them difficult to steal. Canina’s intuition represents a very modern understanding of a cultural route, because through the restoration of its monuments becomes a museum in itself. It is on the interpretation of the protection and conservation approach, that Canina expressed in a modern and creative form — an idea that was greeted by a great public appreciation of his contemporaries – that we concentrated our study.

When it came to our restoration of Canina’s work we closely followed his documentation and the extremely accurate surveys he had carried out at the time, with a study we undertook at the National Archives of Turin, were these sources are deposited. These documents faithfully reported the topographical positions in which each finding was discovered, itemising them one by one in notebooks, for each side of the road.

Fig. 4 3D reconstruction of the tomb of Hilarus Fuscus (University of Ferrara School of Architecture 2000)

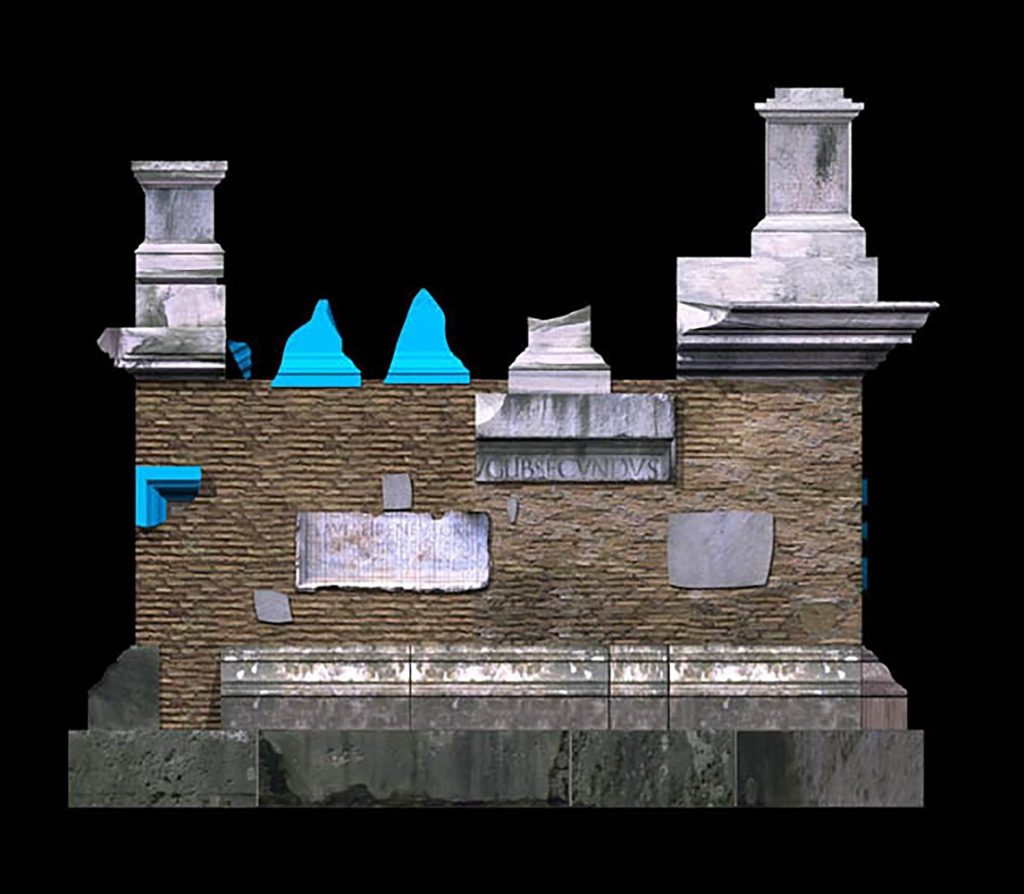

In 1998, working with the University of Ferrara, 3D reconstruction drawings were prepared of these eight tombs (Fig. 4). After making an assessment in situ of the current state of conservation of the findings that Canina had selected, they were put back in place (Filetici, Pasquali 2000). We substituted the stolen pieces placing in the spaces left empty slabs of line-chiselled travertine. After cleaning and protecting the surfaces of the eight tombs, we erected a stone sign on each one bearing its name and the date on which its restoration was completed.

Thus, it can be said that this was a restoration of a restoration to which the technical knowledge of today was applied to preserve Canina’s open-air museum and his farsighted “compositional” approach to the protection of monuments.

In carrying it out we developed a new dialogue between archival work, restoration, historical research, and the existing architecture in a holistic approach that we decided to dedicate to the late Paolo Mora in the hope that our restoration of a restoration may offer useful suggestions for the discipline and for other future restoration work on the Via Appia.

At Casal Rotondo, Canina created a wonderful work by erecting an undulating surface of brick masonry on which he displayed curvilinear marble blocks from the nearby tomb (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 The undulating brick backdrop at Casal Rotondo, created by L. Canina (Photo: G. Carpignoli 2018)

In the vast panorama of the conservation of ancient heritage, Canina’s project was a masterpiece of design that clarifies, without hesitation, how an architectural project can resolve specific problems in great panorama of heritage conservation and can, therefore, be taken as a significant example from which to learn in carrying out today’s more extensive upgrading programme for the “Appia Regina Viarum” project.

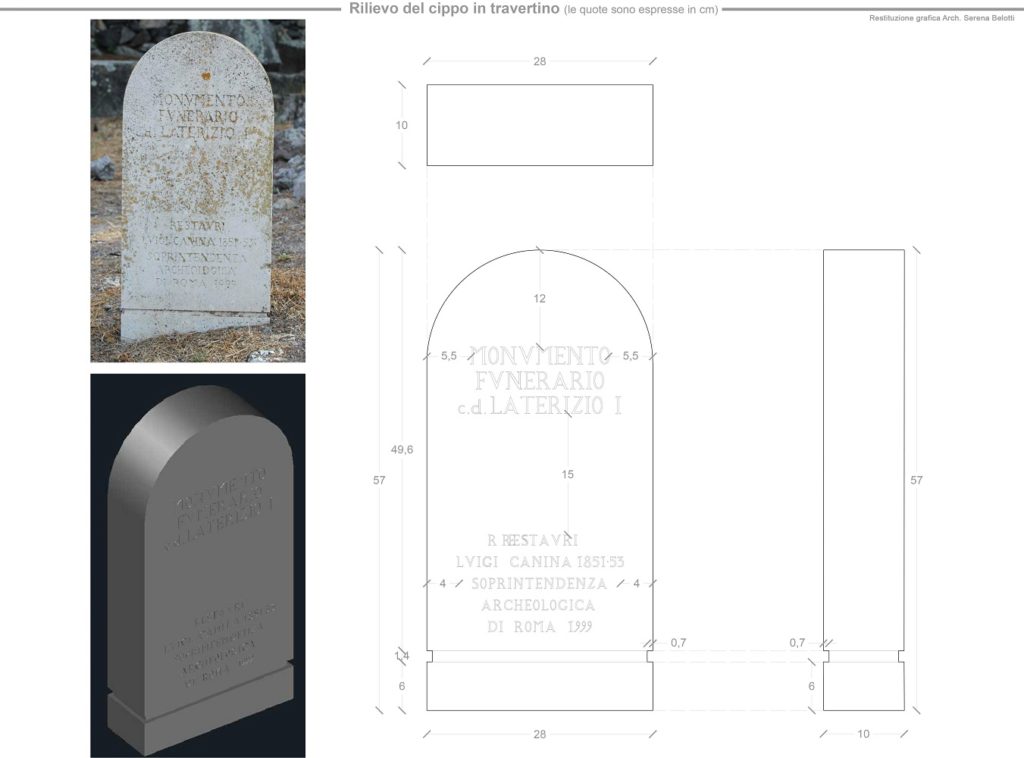

Referring to Canina’s published works we redesigned a travertine milestone to be positioned near the eight restored tombs, bearing the names of the monuments and their date of restoration. This milestone (Fig. 6) was selected as a sign for the walking trail of the “Appia Regina Viarum” project.

In light of the wide range of our experiences described here, we do not believe that ancient heritage can be restored according to standardised practices; instead we would emphasise that proceeding on a case-by-case basis is more suitable considering the multiplicity and variety of this great monumental heritage.

Our decision to use compatible materials and traditional techniques has confirmed itself as the most suitable direction in which restoration should proceed in order to avoid modifying the construction equilibrium of a building or its structural typology. In fact, if the state of conservation of any ancient monument or building is to be correctly understood, it is essential to reconstruct the history of how it was transformed over time, and the impact of those alterations on its general stability.

At the Tomb of Gallienus (Fig. 7) we reconstructed the barrel vaults at the lower level re-establishing the group of masonry that was missing and the support for the structural masses above, which previous collapses had left unsupported.

Fig. 7 The so-called Tomb of Gallienus. Reconstruction of the vaults and seismic improvement restoration works, carried out by Ettore Palmucci. Project by M.G. Filetici and C. Baggio, 2016 (Photo: S. Belotti 2017)

The roof of the columbarium in the so-called “sepolcro a staffa” tomb, where terracotta cinerary urns and floor mosaics are still preserved in situ, was restored.

In the octagonal tomb (Fig. 8) on the opposite side of the road, at the great Nymphaeum of the Quintili Villa, portions of the vaults were reconstructed to support the cementitio conglomerate masonry, which had been left without adequate support and was found to be in a dangerous condition. The ancient internal spiral staircase in opus reticolatum was completed and confirmed in its load-bearing function for the structure surrounding it.

The original external finish of many of the tombs has long been lost, leaving the underlying surface in cementitio permanently and irreparably exposed to: wind from the north-east, humidity that is carried from the sea in the west, the changing weather conditions, the growth cycles of the plants, and to the dangers caused by drought or sudden heavy rain. Essential works were, therefore, undertaken to ensure that the exteriors are all correctly conserved in the future by botanically verifying the plant types growing around them and making their rainwater disposal systems effective.

One of the key elements of the Via Appia restoration was to ensure that a careful programme of ordinary planned maintenance will be carried out (Alberti, Filetici et al. 2005). For that purpose we prepared an extensive maintenance project, already tested over a number of years, based on cataloguing the artefacts subdivided by size, masonry type, priority, level of risk, etc.. On the basis of necessity are settled the frequency of the interventions, the methods for carrying them out, the techniques to be used, and their costs. Annually, the Superintendence, besides ensuring ordinary planned maintenance to major architectural complexes and the landscape, it also guarantees specific maintenance to 66 tombs in rotation, based on a priority assessment. Obviously this important and necessary maintenance programme is subordinated to the annual budget.

For more than 25 years the Archaeological Superintendence of Rome has been operating this methodological approach in continuity, not always being able to count on significant financial resources but always on the basis of scientific programmes for intervention. These programmes form part of the general multi-disciplinary plan, which takes as its starting point our studies of the outstanding work of Luigi Canina and makes use of the new scientific and technical restoration knowledge. As a clearly practicable reality for implementation and development, the “Appia Workshp” is representative of that plan.

Arch. Maria Grazia Filetici

Parco Archeologico del Colosseo

(The article is from “China and Italy: routes of culture, valorisation and management” , CNR 2018, edited by Heleni Porfyriou and Bing Yu)