The “Via Appia” construction started in 312 B.C., at the height of the second Samnite war, a crucial period of the history of Rome that had recently suffered the bitter humiliation of the Caudine Forks (321 B.C.).

The Road was named in honour of its creator, the censor Appius Claudius Caecus, “the Blind”, an enlightened and ambitious member of the administration and an advocate of the expansion of Roman domination into the southern regions of ancient Italy. He conceived the project to connect Rome with Capua (today’s Santa Maria Capua Vetere) in order to allow fast movements of armed troops in the heart of the territories inhabited by Oscan populations.

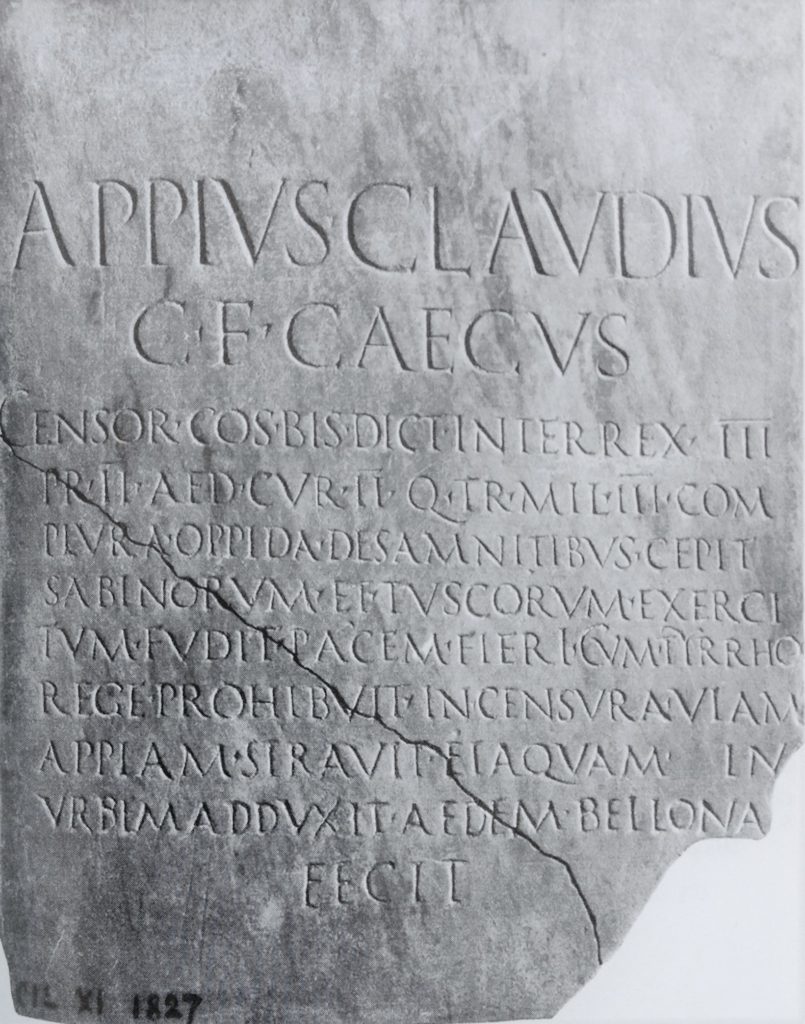

Elogium d’Appius Claudius Caecum (inscription on marble found in the forum of Arezzo, now at the Archaeological Museum of Florence – photo MiBACT) – Appio Claudio the Blind, son of Caio, censor, twice consul, dictator, three times senator with supreme power, twice pretore, twice edile curule, questore, three times military tribuno, conquered many Sannitic fortresses, caused the defeat of both Sabini and Etruscan armies, was against the peace with King Pyrrhic, when he was a censor he built the Appia Way, brought water to the city (of Rome), and built the temple of Bellona.

The Roman expansion towards south had already started with the first Samnite war (343-341 B.C.) contrasting the Samnite people aims in the same direction and resulting in the submission of Capua, granted with the citizenship without voting rights (civitas sine suffragio). Once a rich and powerful Etruscan town, Capua was at the head of the League formed by the Campani cities on the northern part of modern Campania. Rome had concentrated its attention on this fertile and wealthy region inhabited by this Oscan population, just like the Samnites.

The construction of the Via Appia at an advanced stage of the second Samnite war (327-304 B.C.) marked the consolidation of the expansion project.

During the third Samnite war (299-290 B.C.) the Latin colonies of Minturnae (Minturno) (295 B.C.) and Sinuessa (Mondragone) (296 B.C) were established to defend both the important border of the Garigliano river and, indeed, the route of the Appia that formed the decumanus maximus, the main street of these towns. The colony of Venusia (Venosa) was established a few years later (291 B:C.) to control the wide area South of the Ofanto river and in a strategic position on the border between Irpinia, Lucania and Apulia.

In 268 B.C., when the union and the resistance of the Samnite populations had been completely vanquished, Romans established the Latin colony of Malventum, the capital city of the Hirpini Samnite tribe, and renamed it Beneventum (Benevento). Emphasizing its strategical role, also in this case the Appia formed the decumanus maximus of the city continuing its route South.

Probably the design of the project extension was maturing by then, including Taranto, the glorious Greek colony subjected a few years before (272 B.C.), and targeting Brundisium, bridgehead to the East, where a new colony was established (246-243 B.C). Supposedly the foundation of the colony in Beneventum and the extension of the route to Taranto were part of a single project that was not achievable before, crossing a territory full of obstacles and hostile populations.

Conceived for a military use, the road marks and follows Rome’s power gradually rising through the extreme southern regions of the Italian peninsula. The extension to Brindisi probably was planned after the establishment of the colony and the end of the first Punic war (241 B.C.). In fact the clash with the Fenicians had highlighted the need of fast routes in the Mediterranean Sea, leading to the completion of the project presumably in between the first and the second Punic war (241-219 B.C.).

The long course of the Via Appia gives a concrete representation of the consolidation and realization of a great dream. After the Punic wars, Roman could set off the conquest of the Balcanic peninsula and Asia Minor.

At it’s final completion, the Via Appia, regina viarum, as named by the Roman poet Publius Papinius Statius, measured 364 Roman miles (530km).

The relevance of the Appia is testified by the attention reserved to it by rulers at different times. Many emperors binded their name to great restoration and enhancement plans and many milestone inscriptions remind us these events. Important examples were Traianus and Nerva, while Iulius Caesar and later Marcus Aurelius backed the restorations with their own wealth. Even Teodorico, king of the Goths, promoted a restoration along the Decennovium, the canal running abreast the Appia in the Pontina plane.

The columns of Brindisi (the right column is a virtual reconstruction. Scenes from the 2007 video made by Digitarca and SIT Territorial Information Systems)

At the mid of the VI century A.C. Procopius in the history of the Gothic Wars, De bello Gothico, still praised the perfect state of the Road. The Appia was therefore scene of Barbarian raids and later on of pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Surviving all these tormented centuries until our times, many segments of the Road were abandoned, branching out in different trails to overcome temporary obstacles. In any case, also if in time it underwent several resettlements that resulted in the abandonment of different portions, the role of principal connection route from Rome to Brindisi was never neglected. Finally a new route, only partially following the ancient one, is still running today, the SS 7.

(A head image of Appio Claudio blind in the senate – fresco by Cesare Maccari – Palazzo Madama, Rome)

of Giuliana Tocco Sciarelli